Memoirs usually take the form of a narrative, The terms memoir and autobiography are commonly used interchangeably, and the distinction between these two genres is often blurred. In the Bedford Glossary of Critical and Literary Terms, Murfin and Ray say that memoirs differ from autobiographies in 'their degree of outward focus. This memoir’s narrative includes Winterson’s search for her birth mother and the author’s self-invention, her intellectual development. The device of the trapped young person saved by books. A memoir is a narrative, written from the perspective of the author, about an important part of their life. It’s often conflated with autobiography, but there are a few important differences. An autobiography is also written from the author’s perspective, but the narrative spans their entire life. A memoir can certainly possess narrative and dramatic elements even if the story it tells is not as vividly and concretely dramatic as a Hollywood film. If a memoir is not a screenplay, that doesn’t mean the writer must simply give up and say, Well, then, there’s no need to try to find a narrative. Narrative (Common Core Standard W.7.3) writing is writing that tells a story. (One way to remember this is to think of what the narrator of a story does - he or she tells the story, right?) A memoir is a narrative form of writing in which the writer relates a true event, incident, or experience in his or her own life. Although the events of a.

Narrative therapy uses a client’s life story to shine a spotlight on how he understands his experience. The concept of an “illness narrative” emerged not in a literary context but over the past two decades in the fields of psychotherapy and medicine. I have pondered illness narratives from the point of view of a depressed parent with a profoundly sick child, and I have examined them from the perspective of a professional writer and teacher of memoir. It is my belief that ideas that have developed within the field of medicine about these narratives can help those who wish to write powerful stories about their own – or others’ – illnesses.

Illness narratives and healing

In medical schools, the illness narrative concept has been applied to the training of doctors, teaching them to communicate better with patients by understanding the various meanings patients give their illnesses and helping them change their narratives toward more successful outcomes. Through this adaptation in a clinical setting, it’s been found that a patient’s choice of illness narrative can have a real impact on treatment and survival.

Studies show, for example, that when a wife includes her husband in the story of her breast cancer, in effect changing the protagonist in her narrative from “I” to “we,” treatment becomes more effective and her chance of survival improves. In psychotherapy, when a client sees a redeeming value in the abuse he suffered in childhood – usually that the hardship has made him a stronger person – studies by Dan P. McAdams show that this “redemption narrative” provides the client a higher level of life satisfaction.

As a memoirist and teacher of memoir writing, my major focus for understanding and applying the illness narrative concept is in my writing and teaching life. Many memoirs, including my own (“A Lethal Inheritance”), chronicle one person or family’s experience of mental illness. Given their popularity, these psychologically driven true-life accounts define much of our cultural representations of mental illness. These accounts also follow certain templates that help determine the narrative arc of the stories being told.

The wounded storyteller

Arthur W. Frank is a sociologist who first developed the concept of the illness narrative in his influential book “The Wounded Storyteller: Body, Illness, and Ethics.” Using his own cancer and recovery as inspiration, he begins by describing life as a journey and serious illness as a “loss of the destination and map that had previously guided the ill person’s life.” He emphasizes that “Ill people learn by hearing themselves tell their stories, absorbing others’ reactions and experiencing their stories being shared.”

Frank views an illness narrative not as an externalized construct but as an interactive experience that the ill person enters. From within this story, the patient then finds others – patients like himself, medical providers, caregivers – with whom he interacts, using the illness as a primary focal point for those interactions. How family and friends react to an illness affects the stories a patient tells himself and others. For mental illnesses, addictions, or the more mysterious physical sicknesses – for example, chronic pain syndrome – there is often a stigma attached. This stigma can then shape our personal narratives by adding guilt or shame to the mix, which in turn can make someone avoid treatment, stymie recovery. In a literary context, these sentiments turn us into unreliable narrators.

Three common plot lines for an illness narrative

Frank defined three types of illness narratives, seeing them as the framework or plotline that the ill person uses first to understand and then to explain her illness. If you are writing a story about illness, you will probably discover that one (or more) of the following three narratives mirrors the storyline you once lived or are now telling about someone else.

The restitution narrative

This is the most familiar and socially condoned type of illnessnarrative. A restitution narrative tells the story of a patient being restored to good health due to the marvels of modern medicine. These are the gee-whiz recovery storiesthat we often read about in the popular press. In this story model, the illness is seen as transitory. As Frank put it, “It [the patient’s thoughts, feelings, and actions] is a response to an interruption, but the narrative itself is above interruption.” It is all about the body returning to its former image of itself, before illness. The illness has been managed, the body likened to a car that has broken down and been repaired. If, for example, you had one of the many types of cancer that now have a high rate of remission with early treatment, or a mental disorder that responds well to a brief course of therapy or medication, a restitution illness narrative could be the appropriate plot structure for your story.

The chaos narrative

In contrast, the narrator in a chaos illness narrative takes a radically different and more unsettled path. The illness moves randomly, so the patient goes in a zigzag story line, one that progresses from bad to worse and back to bad before getting worse again. The storyteller may be without hope; he imagines his body and life never improving.

If you construct a memoir about your years in a downward spiral dealing with a more mysterious ailment such as chronic fatigue syndrome or a case of major depression that doesn’t respond to antidepressant therapy, you would probably be writing a chaos narrative. Chaos narratives describe the experience of having a disease with no cure and perhaps only unreliable treatments. It is the story of AIDS in the ’80s and early ’90s. It also describes the old medical model used for treating severe mental illness or long-term addiction, which aimed for maintenance, not improvement, as the goal of treatment. For many in mental health care, this old model has been replaced by a recovery model. A patient shifting between these models can be seen as moving from a chaos narrative to a quest narrative.

The quest narrative

Frank described the quest illness narrative as when “the ill person meets suffering head on; they accept illness and seek to use it. Illness is the occasion of a journey that becomes a quest.”

The narrator in a quest narrative shows us what it’s like to be in pain. She shares her hopes, and fears, and sense (or lack of sense) about the meaning of suffering and the possibility of death. Rather than telling others what they should do in order to return to their former state, quest narratives bear witness to the experience and share wisdom. It’s not that the person doesn’t wish to be well. She might in fact achieve wellness; but, more importantly, she accepts what is. Wellness is not defined as the state the ill person occupied before the illness struck. It represents the claiming by the narrator of a newer, wiser state.

Frank demonstrates the quest narrative in action when he writes to his younger self, the person he was before the onset of the testicular cancer that inspired this theoretical work: “For all you lose, you have an opportunity to gain: closer relationships, more poignant appreciations, clarified values. Your are entitled to mourn what you can no longer be, but do not let this mourning obscure your sense of what you can become. You are embarking on a dangerous opportunity. Do not curse your fate; count your possibilities.”

If you’re writing a memoir about an experience of medical or mental illness, it’s important to think through whether your plotline fits one of the narrative plot structures Frank outlined. Your story may begin with one plot, perhaps restitution, and then, as the illness takes an unexpected turn, become a story marked by chaos.

The illness narrative and the writer-reader experience

The story of mental illness I tell begins as a restitution plot. In 1998 when my then-17-year-old son is diagnosed with schizophrenia, I want only to be told how his doctors plan to “fix him.” When I’m told his disease is incurable, his future bleak, I descend into confusion and fear. This state of chaos gets dramatically worse when acute symptoms of my lifelong depression and a younger son’s anxiety disorder can no longer be denied. Thus what began with single illness in one child becomes an unnamed “family illness” with roots several generations in the past.

When I ultimately reject my son’s bleak prognosis and begin my search for alternatives to the medical model, I change the illness narrative with which I’m framing our now collective experience once more – to the quest plot line. As I wrote my memoir, Arthur Frank’s theoretical work with illness narratives helped me get a handle on how to structure it. This conceptual framework was especially valuable as I asked my readers to trust me on a journey that would take them into an unusual pairing of personal experience and scientific research. In the end I believe it is the power of the personal illness narrative that helps readers digest the often dense research findings.

Example Of A Memoir Paper

It took 10 years for my family to reach recovery and for me to write my memoir.Now that I’ve gone “on the road” to talk with people about my book, I’m struck by the intimacy of the discussions I’m having. The relational nature of the illness narrative concept is strikingly similar to the bond that exists between a memoirist and her readers, especially, I believe, when the focus of a memoir is on a mental illness or addiction. The reader becomes another important player in the particular illness narrative the writer chooses for her story. Does the reader accept the writer’s diagnosis and treatment choices? Are readers rooting for her recovery? The range of possible responses to the mentally ill person’s story in book form mirrors those she encounters on a daily basis in real life. The fundamental fact of the memoir as a record of true experience changes everything about the writing and reading process – bringing it full circle, from life to art and back to life.

Victoria Costello writes popular psychology and blogs at MentalHealthMomBlog.com. Her memoir, “A Lethal Inheritance: A Mother Uncovers the Science Behind Three Generations of Mental Illness,” will be published in Jan 2012. Her “Complete Idiot’s Guide to Writing a Memoir” will appear this December.

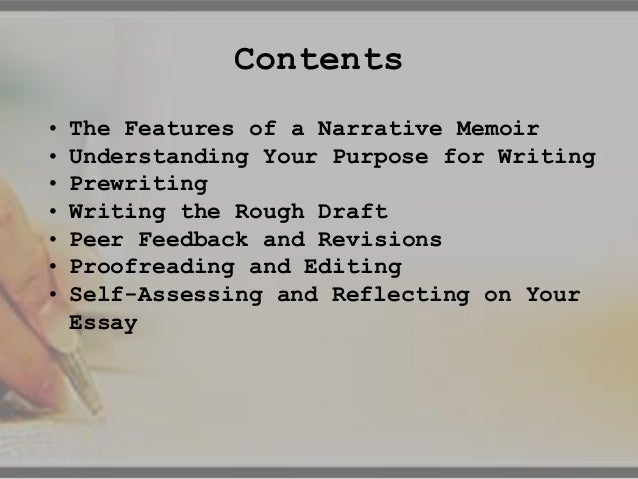

Narrative Memoir

Most popular articles from Nieman Storyboard